Is President-elect Trump’s reaction to the Hamilton cast’s shout out to Vice-President-elect Pence just another example of his ‘deep need to respond to every [perceived] slight’?

Or is it a signpost for where we’re heading? The way we react could have significant implications.

We’re at a point where we need to keep taking the temperature to ensure we notice when it rises.

One possibility: Trump’s response is just more evidence of thin skin and lack of impulse control.

Or, as many people have noted, Trump’s #HamiltonTweets might instead (or also) be a strategic move to distract the public and media from multiple examples of trading on the election to promote his own businesses, as well as the near-admission of wrongdoing when he agreed to pay $25 million dollars to settle the Trump U case. (Or, you know, maybe not.)

But there’s a third explanation. One that we should all consider carefully as we think about what’s next. There’s good reason to worry that @realDonaldTrump intends to inform us that artists are obligated to confine themselves to entertaining.

In case you haven’t seen the rundown of what happened at Hamilton: An American Musical in NYC, Drew McManus has a good summary on his blog. The cast and producers of the show shared this plea with the VPE.

“We, sir — we — are the diverse America who are alarmed and anxious that your new administration will not protect us, our planet, our children, our parents, or defend us and uphold our inalienable rights,” he said. “We truly hope that this show has inspired you to uphold our American values and to work on behalf of all of us.”

The President-elect posted four tweets in response. (He, or someone, deleted one of the four almost immediately.)

The VPE on the other hand seemed to take the curtain call comments with more ease.

He said “It was a joy to be there” and that he wasn’t offended by the comments. Then he remarked, twice, that he would “leave to others whether that was the appropriate venue to say it.” That last part might be important.

Public and Media Reactions

In the days since the curtain call, social and mainstream media have been full of debates over whether the statement was rude or just the cast “taking their shot”, whether the comments should have been made from the stage or elsewhere, as well as speculation about Trump’s motive for reacting as he did.

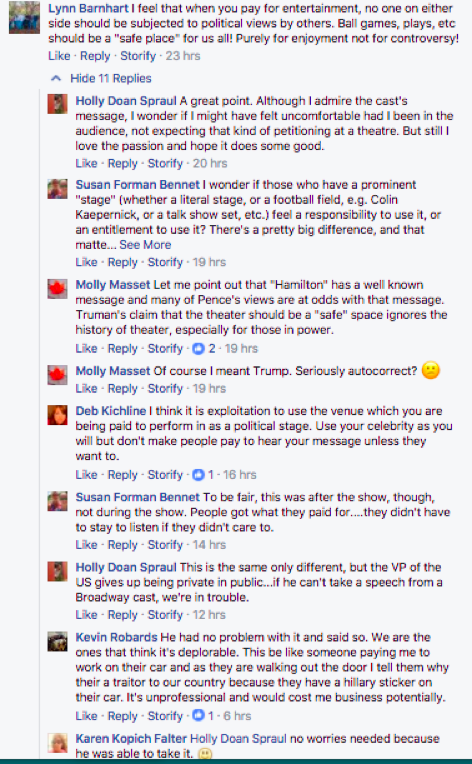

Many commenters made the case that people who are paying for ‘entertainment’ should not be subjected to an artist’s political perspective.

In the days since the curtain call, social and mainstream media have been full of debates over whether the statement was rude or just the cast “taking their shot”, whether the comments should have been made from the stage or elsewhere, as well as speculation about Trump’s motive for reacting as he did.

Many commenters made the case that people who are paying for ‘entertainment’ should not be subjected to an artist’s political perspective.

The panel on MSNBC’s Morning Joe went after the artists for choosing the wrong place to make these remarks. Even Ed Rendell, former chair of the DNC among other theoretically progressive roles, was adamant that the comments should not have come from the stage. “Public officials have to have some space that’s off limits,” he said, relating a story about being booed at a college basketball game with his son.

People Naturally Think of Art as (Just) Entertainment

Here’s the danger. It’s easy to make the case to cut funding for arts when the dominant way of thinking about the arts is as ‘entertainment’ — something other people (mostly rich, white, old people) do. (This was a finding of Topos’ research on how to build broad support for the arts.)

People naturally default to thinking of the arts as one of the things we choose to do with our free time and our money, depending on our taste. Looked at this way, an arts experience is no different from eating out or going to a ball game.

The current debate about whether artists should speak to policy or politics from the stage is framed to reinforce the default thinking about the arts as entertainment.

We see this in reaction to the Hamilton event from commenters on both the left and right: people coming to be entertained shouldn’t be subjected to a political commentary.

Defining Art as Entertainment in Policy

Is it possible that the government would limit public support to art that entertains and does not comment on current events?

David Brooks signaled us when he criticized civic-focused artists in a New York Times column that praised the beauty of art while simultaneously faulting artists who “…prefer to descend to the level of us pundits. Abandoning their natural turf, the depths of emotion, symbol, myth and the inner life, they decided that relevance meant naked partisan stance-taking in the outer world (often in ignorance of the complexity of the evidence).”

It was worrisome last January when Brooks wrote this. Now it seems like a warning.

His framing supports an argument for cutting arts funding and eliminating arts organizations from the charitable deduction altogether, or at best, limiting the deduction so that organizations that create political art or act politically cannot receive deductible donations. (We’ve long been at risk for not being a good fit with the IRS charitable definition anyway.)

Building understanding of the arts as a public good has been the work of many people since 2010 and before — a new focus on building community through the arts is a high priority at the National Endowment, ArtPlace, LISC, The Kresge Foundation, Americans for the Arts, local arts agencies and organizations, and many more.

Our research shows that providing a new way of connecting the dots between the arts and places people want to be can pay off in more support, and in broader understanding of why the arts should receive the benefit of public funding (or public dollars foregone in the form of a tax benefit).

If the new holders of the national microphone choose to frame the arts as just entertainment, they can (at the very least) undermine that nascent understanding of the arts as community builder.

Questions

What now? We’re left with big (huge) questions about where to lay our collective energy and leverage.

Do we put a lot of resources and time into saving the (relatively small) national funding programs, like the National Endowment for the Arts? Is the symbolism of these programs worth the heavy lift despite likely reduced funding levels? If so, how far do we go? What compromises would we have to make to get help from art-loving people with access to the new administration?

What will happen to arts organizations more dependent on public funding and private donations if they defend their right to comment on public policy? The federally supported Holocaust Museum leaders said this recently: “The Holocaust did not begin with killing; it began with words.” Will they be criticized?

Do we continue to put advocacy of the nonprofit arts toward policies important to our communities and democracy, but threatened by the new administration: Obamacare, immigration, Medicaid, equitable development, climate change, programs that provide benefits to people in jobs that don’t pay enough, opposing racism, free speech, free press…. and so on?

Investing a lot of effort into saving art funding streams will look (and be) self-serving. And it diverts valuable energy and resources and power that could affect the outcome on other important issues.

Defining Art as Entertainment in Policy

Is it possible that the government would limit public support to art that entertains and does not comment on current events?

David Brooks signaled us when he criticized civic-focused artists in a New York Times column that praised the beauty of art while simultaneously faulting artists who “…prefer to descend to the level of us pundits. Abandoning their natural turf, the depths of emotion, symbol, myth and the inner life, they decided that relevance meant naked partisan stance-taking in the outer world (often in ignorance of the complexity of the evidence).”

It was worrisome last January when Brooks wrote this. Now it seems like a warning.

His framing supports an argument for cutting arts funding and eliminating arts organizations from the charitable deduction altogether, or at best, limiting the deduction so that organizations that create political art or act politically cannot receive deductible donations. (We’ve long been at risk for not being a good fit with the IRS charitable definition anyway.)

Building understanding of the arts as a public good has been the work of many people since 2010 and before — a new focus on building community through the arts is a high priority at the National Endowment, ArtPlace, LISC, The Kresge Foundation, Americans for the Arts, local arts agencies and organizations, and many more.

Our research shows that providing a new way of connecting the dots between the arts and places people want to be can pay off in more support, and in broader understanding of why the arts should receive the benefit of public funding (or public dollars foregone in the form of a tax benefit).

If the new holders of the national microphone choose to frame the arts as just entertainment, they can (at the very least) undermine that nascent understanding of the arts as community builder.

Questions

What now? We’re left with big (huge) questions about where to lay our collective energy and leverage.

Do we put a lot of resources and time into saving the (relatively small) national funding programs, like the National Endowment for the Arts? Is the symbolism of these programs worth the heavy lift despite likely reduced funding levels? If so, how far do we go? What compromises would we have to make to get help from art-loving people with access to the new administration?

What will happen to arts organizations more dependent on public funding and private donations if they defend their right to comment on public policy? The federally supported Holocaust Museum leaders said this recently: “The Holocaust did not begin with killing; it began with words.” Will they be criticized?

Do we continue to put advocacy of the nonprofit arts toward policies important to our communities and democracy, but threatened by the new administration: Obamacare, immigration, Medicaid, equitable development, climate change, programs that provide benefits to people in jobs that don’t pay enough, opposing racism, free speech, free press…. and so on?

Investing a lot of effort into saving art funding streams will look (and be) self-serving. And it diverts valuable energy and resources and power that could affect the outcome on other important issues.

Working with people to enhance their lives and the places they call home IS the public value of the arts.

Government Controlled Art?

We have to talk about the even darker possibilities. It’s not just the threat to funding or supportive policy. The Nazis decided what true art was and removed art that didn’t match their view of culture. Jews were not allowed to create art. Museum directors were fired, books banned, authors fled. Personal taste became law, which preferenced one race. Government controlled art. It started with small statements. And ended in the murder of millions.

There’s no reason to think we could end up there. But it is time to be very awake.

We have big choices to make…right now.

Government Controlled Art?

We have to talk about the even darker possibilities. It’s not just the threat to funding or supportive policy. The Nazis decided what true art was and removed art that didn’t match their view of culture. Jews were not allowed to create art. Museum directors were fired, books banned, authors fled. Personal taste became law, which preferenced one race. Government controlled art. It started with small statements. And ended in the murder of millions.

There’s no reason to think we could end up there. But it is time to be very awake.

We have big choices to make…right now.

Originally published on Medium November 22, 2016.